Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Practice Guidance

Aim and Purpose

This guidance should be considered in conjunction with other relevant safeguarding guidance, including but not limited to, Multi-agency Statutory Guidance on Female Genital Mutilation (updated 2018)[1], Working Together to Safeguard Children (2018)[2], and additional local procedures and practice guidance available atNorth Yorkshire Safeguarding Children Partnership (NYSCP) and the North Yorkshire Safeguarding Adults Board (NYSAB). This guidance is not intended to replace wider safeguarding guidance, but to provide additional advice on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

Definitions

For the purpose of this guidance, the following definitions apply:

Adult/Woman: ‘Adult’ is defined as a person aged 18 years or over.

Child / Young Person: As defined in the Children Acts 1989 and 2004, ‘child’ means a person under the age of 18. This includes young people aged 16 and 17 who are living independently; their status and entitlement to services and protection under the Children Act 1989 is not altered by the fact that they are living independently.

Key points:

FGM is illegal in England and Wales under the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003[3].

As amended by the Serious Crime Act 2015, the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 now includes:

- An offence of failing to protect a girl from the risk of FGM,

- Extra-territorial jurisdiction over offences of FGM committed by abroad by UK nationals and those habitually (as well as permanently) resident in the UK,

- Lifelong anonymity for victims of FGM,

- FGM Protection Orders (FGMPOs) which can be used to protect girls and women at risk (see FGMPO Factsheet), and

- A mandatory reporting duty which requires specified professionals to report known cases of FGM in under 18s to the police.

In England and Wales, criminal and civil legislation on FGM is contained in the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003

What is Female Genital Mutilation?

The World Health Organisation defines FGM as “…all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons”.

The Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 (as amended) narrows the definition of FGM to not include:

- a surgical operation on a girl that was necessary for her physical or mental health, or

- a surgical operation on a girl who was in any stage of labour, or had just given birth, for purposes connected with the labour or birth

It is frequently a very traumatic and violent act of the victim and can cause harm in many ways. The practice can cause severe pain and there may be immediate and / or long-term health consequences, including mental health problems, difficulties in childbirth, causing danger to the child and mother; and / or death.

The age at which FGM is carried out varies enormously according to the community. The procedure may be carried out shortly after birth, during childhood or adolescence, just before marriage or during a woman’s first pregnancy.

FGM is a criminal offence – it is child abuse and a form of violence against those subjected to it, and therefore should be treated as such. Cases should be dealt with as part of existing North Yorkshire structures, policies and procedures on child protection (see, “Worried about a child?” and NYSCP Procedures) and the “Joint Multi-Agency Safeguarding Adults Policy and Procedures” for safeguarding adults. There are, however, particular characteristics of FGM that front-line professionals should be aware of to ensure that they can provide appropriate protection and support to those affected.

Legislation and Policy

The Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 (with amendments from the Serious Crime Act 2015) makes it a criminal offence to:

- Excise, infibulate or otherwise mutilate the whole or any part of a female’s labia majora, labia minora or clitoris (subject to limited exemptions for mental or physical health)

- Aid, abet, counsel or procure a female to excise, infibulate or otherwise mutilate the whole or any part of her own labia majora, labia minora or clitoris, or

- Aid, abet, counsel or procure a person who is not a United Kingdom national or permanent United Kingdom resident to do a relevant act of female genital mutilation outside the United Kingdom

- This Act has extra-territorial extensions, i.e. if a person commits any of the above offences in another country it would be treated as if the offence had occurred in the United Kingdom. A person convicted of an offence under the FGM Act 2003 is liable to imprisonment between six months and fourteen years.

If a female genital mutilation offence is committed against a child under the age of 16, each person who is responsible for the child at the time FGM took place is also guilty of an offence. A person is ‘responsible’ for a child if they have parental responsibility for and frequent contact with the child or the person is over 18 years of age and has assumed (and not relinquished) responsibility for caring for the child in the manner of a parent.

What are the types of FGM?

| Type | Description | |

| 1 | Clitoridectomy | Partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals) and, in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris). |

| 2 | Excision | Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (the labia are “the lips” that surround the vagina). |

| 3 | Infibulation | Narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the inner, or outer, labia, with or without removal of the clitoris. |

| 4 | Other | All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area. |

Identifying a person at risk of FGM

Where a person is thought to be at immediate risk of FGM taking place or about to take place, practitioners must be alert to the need to act quickly before the person undergoes FGM either in the UK or abroad.

Indications that FGM may be about to take place:

- The family comes from a community that is known to practice FGM (it may also be possible that they will practice FGM if a female family elder is around);

- Parents requesting permission for their child to be taken out of school two weeks before or after the summer holidays (recovery period can be up to 8-10 weeks);

- A person talking about a long holiday to her country of origin or another country where the practice is prevalent

- A child talking about ‘becoming a woman’ or ‘rites of passage’

- A child talking about new clothing or special outfits

- A child may confide in a professional that they are about to undergo a “special procedure” or attend a special occasion

- Becoming withdrawn or acting out of character

- There are older females in the family (e.g. older sister/s, mother) who have undergone FGM

- Any female child born to a woman who has been subjected to FGM must be considered to be at risk, as must other female children in the extended family

- Any female who has a sister who has already undergone FGM must be considered to be at risk, as must other females in the extended family

- A relative or ‘cutter’ visiting from territories known to practice FGM

- Running away or planning to run away from home.

Identifying a person who has been subject to FGM

Indications that FGM may have already taken place:

- A child may spend long periods of time away from the classroom during the day with urinary or menstrual problems if they have undergone Type 3 FGM. Frequently females who have undergone FGM find it harder to urinate and it will therefore take longer to pass urine

- There may be prolonged absences from school with noticeable behaviour changes on the child’s return

- A child requiring to be excused from physical exercise lessons without the support of their GP and very often using the excuse that females of her faith can’t exercise

- A child may confide in a professional or ask for help

- Asking for help, and or needing extra support but not being explicit about what the problem is

- Difficulty walking, sitting or standing.

- Reluctance to have routine medical examinations.

Professionals encountering a person who has undergone FGM should be alert to the risk of FGM in relation to:

- Younger siblings;

- Daughters they may have in the future;

- Extended family members.

Responding to a child / young person who is at risk or who has been subject to FGM

The appropriate response to FGM whether at risk or who has been subject to the procedure is to follow safeguarding procedures to ensure:

- Immediate protection and support for the child / young person; and

- That the practice is not repeated with other members of the family, household or community, including any unborn children.

In addition, an appropriate response to a person who is at risk of FGM can include:

- Seeing the person on their own and creating an opportunity for them to disclose further information

- Using simple language and straightforward questions

- Using terminology that the person will understand e.g. the person may not view the procedure as an illegal practice

- Being sensitive to the fact the person may be loyal to those who subjected them to the procedure

- Arranging for an interpreter if this is necessary and appropriate (interpreters must be made aware of the subject they will be covering and that they are comfortable with this) – for further information regarding interpreters please contact the Customer Resolution Centre on 01609 780780

- Allowing the person time to talk

- Getting accurate information about the urgency of the situation, if the person is at risk of being subjected to the procedure

- Informing the person how they contact you again

An appropriate response by professionals who encounter a person who has undergone the procedure of FGM includes:

- Being sensitive to the intimate nature of the subject

- Making no assumptions

- Asking straightforward questions

- Being ready to listen

- Being non-judgemental (condemning the illegal practice, but not blaming the person)

- Understanding how they may feel in terms of language barriers, cultural differences, that they, their partner, their family may feel they are being judged

- Being able to explain that FGM is illegal and that discussing this with you, can be used to help protect them and help prevent the illegal practice of FGM taking place in the future.

- Arranging for a professional interpreter (interpreters must be made aware of the subject they will be covering and that they are comfortable with this).

General advice when approaching those who may have undergone FGM or are at risk of FGM

Other useful advice when speaking to a person who may have undergone FGM or parents of a child you believe could be at risk includes:

- Using appropriate terms

- Approach the subject sensitively

- Where an interpreter is needed, a female interpreter is essential – a family or community member must not be used to translate

- Be aware that re-infibulation (after childbirth) is also illegal.

Responding suitably is key, so that the appropriate immediate protection and support can be provided. Furthermore, responding appropriately will disseminate a message in communities that the illegal practice of FGM is taken seriously and agencies are responding to FGM in a sensitive and robust way.

Mandatory Reporting Duty for all Professionals who identify FGM

All professionals (i.e. a teacher, social worker or healthcare professional) who in the course of their work, believe that an act of FGM appears to have been carried out on a person who is aged under 18 years must notify the police. This includes cases where:

- A child or young person has told a professional that an act of FGM (however described) has been carried out on them, or

- The professional has observed physical signs indicating female genital mutilation has been carried out and the professional has no reason to believe that the act was part of:

- a surgical operation on a female which is necessary for her physical or mental health, or

- a surgical operation on a female who is in any stage of labour, or has just given birth, for purposes connected with the labour or birth

The professional who identifies FGM in a female under 18 years must call 101 to make a report. When making an FGM notification to the police the professional must have details of:

- Person’s name, date of birth and address

- Name and contact details of the professional

- Name and contact details of the local safeguarding lead – Midwifery or Adult Safeguarding Lead

It is best practice when making notifications to the police to ensure:

- The notification is made on the same working day as FGM was identified calling via 101 to make a report

- Local safeguarding lead within your organisation is updated within one day

- All decisions and actions taken are recorded

If you believe that the person is in immediate danger you must act immediately, which may include calling 999. Mandatory reporting is only one part of safeguarding against FGM. Always ask your safeguarding lead if in doubt.

If the woman is over 18 when she discloses/FGM is identified, the mandatory duty to report does not apply and you should follow local safeguarding adults procedures

In all cases, professionals should also consider whether there are other people within the household, extended family and community who may be at risk of or may have been subject to FGM and whether anyone should be referred to the Children and Families Service. If the professional identifies an adult at risk of, or having been the subjected to FGM, local safeguarding adults procedures should be followed.

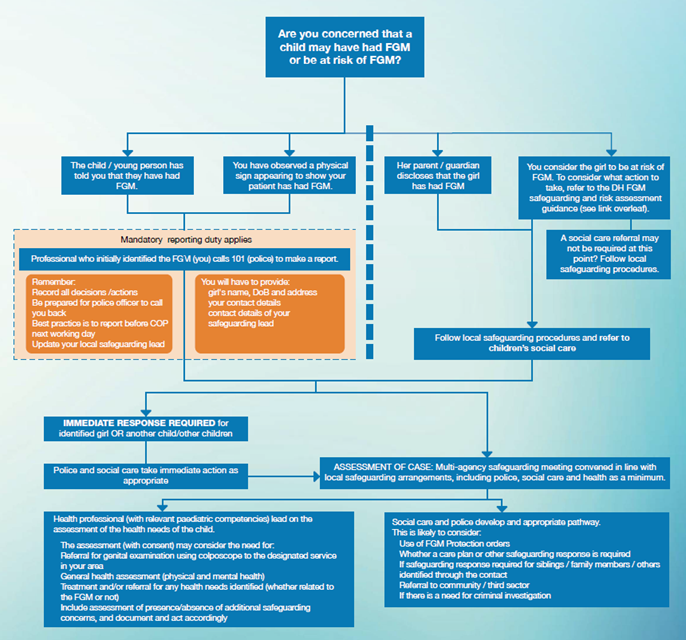

Below illustrates the local procedures to be followed if there is a child / young person identified who has undergone FGM or is at risk of FGM.

FGM Local Procedure

When a child or young person is identified who has undergone FGM or is at risk of FGM

Additional Guidance for NHS Staff

The Department for Health has produced additional guidance for NHS organisations so they can meet the requirements to collect and submit data about patients with FGM.

The guidance relates to the Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Enhanced Dataset by the Health and Social Care Information Centre and the forthcoming professional duty about FGM to be published October 2015. The following organisations are required to have regard to the FGM Enhanced dataset standard from October 2015:

- General Practice

- Mental Health Trusts

- Acute Trusts (mandatory since 1 July 2015)

Sexual health and GUM (Genito-Urinary Medicine) clinics, where patients do not have to provide their personal information, are out of scope, but these services are nonetheless reminded of their responsibilities to share information to ensure appropriate safeguarding responses are put in place every time this becomes necessary.

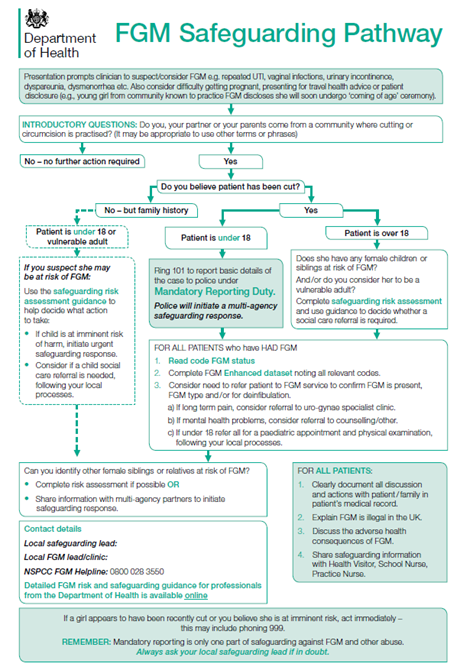

The flowchart below from the Department of Health outlines the FGM Safeguarding Pathway for NHS staff which includes mandatory reporting and reporting for the enhanced FGM dataset:

The data collected is sent to the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC), where it is anonymised, analysed and published in aggregate form. Personal information is only collected as part of the FGM Enhanced dataset for internal data quality assurance and to avoid duplicate counting. A woman or child’s personal details will never be published in the national aggregate reports and will never be passed to anyone outside HSCIC. This work specifically will not pass any personal details to the police or social services -the collection of this data will not trigger individual criminal investigations.

Further information can be accessed from:

Support Services

If you or the person you are concerned about is in danger and immediate action is required, you should ring the emergency services on 999.

If you have concerns about a person and you wish to speak to someone or make a referral, please use the following contacts:

North Yorkshire County Council Customer Resolution Centre:

Open Monday to Friday 9.00am to 5.00pm

All areas: 01609 780780

Emergency Duty Team (all other hours): 01609 780780

For making a referral for a child under 18 years of age, please visit the NYSCP website at:

For making a referral for an adult 18 years or older, please visit the NYSAB website at:

North Yorkshire Police

Call 101 to make a mandatory report of FGM to the police where a female under 18 years of age has disclosed or you have observed FGM has taken place. If a child is in immediate danger call 999.

Appendix – Additional Guidance on FGM

Cultural Underpinnings

Female genital mutilation is underpinned by a mix of cultural and social factors within families and communities.

- Where FGM is a social convention, the social pressure to conform to what others do and have been doing is a strong motivation to perpetuate the practice

- FGM is often considered a necessary part of raising a child, and a way to prepare them for adulthood and marriage

- FGM is often motivated by beliefs about what is considered proper sexual behaviour, linking procedures to premarital virginity and marital fidelity. FGM in many communities is believed to reduce a woman’s libido and therefore believed to help her resist “illicit” sexual acts. When a vaginal opening is covered or narrowed (Type 3 FGM), the fear of the pain of opening it, and the fear that this will be found out, is expected to further discourage “illicit” sexual intercourse among females with this type of FGM

- FGM is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that females are “clean” and “beautiful” after removal of body parts that are considered “male” or “unclean”

- Though no religious scripts prescribe the practice, practitioners often believe the practice has religious support

- In most societies, FGM is considered a cultural tradition, which is often used as an argument for its continuation

- In some societies, recent adoption of the practice is linked to copying the traditions of neighbouring groups. Sometimes it has started as part of a traditional revival movement

- In some societies, FGM is practised by new groups when they move into areas where the local population practice FGM

Piercings, Tattoos and Vaginal Modification

Vaginal modification including piercings, tattoos and other modifications are increasingly common and can be lifestyle choices by individuals. However, practitioners need to be aware that such modifications may be also classed as Type 4 Female Genital Mutilation. When considering whether a female is at risk of FGM practitioners should consider whether they were able to consent to the procedure and if that consent was not forced or coerced. Practitioners should also consider the extent to the modification (if known). It should be noted that females under 18 years of age would not normally be able to consent to vaginal modification, including piercings and tattoos.

Names for FGM

FGM is referred to by many names including female cutting and female circumcision, (the latter being an expression which implies the practice is similar to male circumcision). The degree of cutting is far more extensive than male circumcision and the procedure often impairs a woman’s sexual and reproductive functions and ability to pass urine normally.

Terms Used for FGM in other Languages

| Country | Term used for FGM | Language |

| CHAD – the Ngama Sara subgroup | Bagne Gadja | |

| GAMBIA | Niaka Kuyungo Musolula Karoola | Mandinka Mandinka Mandinka |

| GUINEA-BISSAU | Fanadu di Mindjer | Kriolu |

| EGYPT | Thara Khitan Khifad | Arabic Arabic Arabic |

| ETHIOPIA | Absum Megrez | Harrari Amharic |

| ERITREA | Mekhnishab | Tigregna |

| IRAN | Xatna | Farsi |

| KENYA | Kutairi Kutairi was ichana | Swahili Swahili |

| NIGERIA | Ibi/Ugwu Didabe fun omobirin/ ila kiko fun omobirin | Igbo Yoruba |

| SIERRA LEONE | Sunna Bondo Bondo/sonde Bondo Bondo | Soussou Temenee Mendee Mandinka Limba |

| SOMALIA | Gudiniin Halalays Qodiin | Somali Somali Somali |

| SUDAN | Khifad Tahoor | Arabic Arabic |

| TURKEY | Kadin Sunneti | Turkish |

Details from FORWARD

International Prevalence of FGM

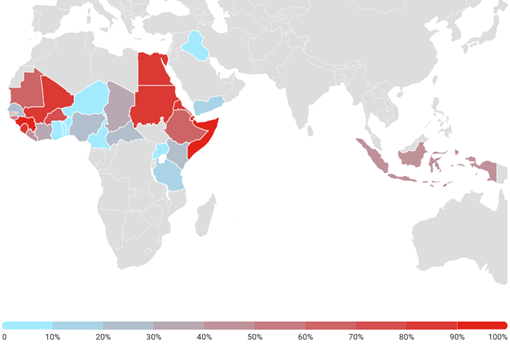

FGM is a deeply rooted practice, widely carried out mainly among specific ethnic populations in Africa and parts of the Middle East and Asia. It serves as a complex form of social control of a women’s sexual and reproductive rights. The exact number of children and adults alive today who have undergone FGM is unknown, however UNICEF estimates that over 200 million children and women in 31 countries, across three continents have undergone FGM, with more than half of those subjected living in Egypt, Ethiopia and Indonesia..

The heat map below shows some of the most prevalent areas of Africa where FGM is practiced. More information can be obtained from Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Statistics published by UNICEF.

List of countries where female genital mutilation is prevalent

African RegionAsian CountriesArabian PeninsulaOther Areas

Prevalence of FGM in England and Wales

The prevalence of FGM in England and Wales is difficult to estimate because of the hidden nature of the crime. However, the Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Enhanced Dataset (SCCI 2026) supports the Department of Health’s FGM Prevention Programme by presenting a national picture of the prevalence of FGM in England.

- There were 1,855 individual women and girls who had an attendance where FGM was identified in the period between January 2020 and March 2020. These accounted for 2,935 attendances reported at NHS trusts and GP practices where FGM was identified.

- There were 860 newly recorded women and girls in the period between January 2020 and March 2020. Newly recorded means this is the first time they have appeared in this dataset. It does not indicate how recently their FGM was undertaken, nor does it mean that this is the woman or girl’s first attendance for FGM. The number of newly recorded women and girls has reduced over time. This is to be expected as the longer the collection continues, the greater the chance of a women or girl having been recorded in it previously.

- Between January 2020 and March 2020, 91 NHS trusts and 23 GP practices submitted one or more FGM attendance records.

Consequences of FGM: Short & Long term Implications, Mental Health & Wellbeing

FGM can cause a range of short-term and long-term health issues. The nature of the health implications arising from FGM are linked to the degree of the cutting, the cleanliness of the tools used to do the cutting, and the health of the person receiving the cutting.

In most countries, FGM is performed in unclean conditions by mainly traditional practitioners who may use scissors, razor blades, or knives. However, in some countries like Egypt, up to 90% of FGM is performed by a health care professional.

Short-Term Health Implications:

- Bleeding or hemorrhaging: If the bleeding is severe, the person can die.

- Infection: The wound can get infected and develop into an abscess (a collection of pus). A person can develop fevers, sepsis (a blood infection), shock, and may die, if the infection is not treated.

- Pain: People are routinely cut without first being numbed or having anaesthesia. The most extreme pain tends to occur in the aftermath of the procedure.

- Trauma: People are held down during the procedure, which can be physically and psychologically traumatic.

Long-Term Health Implications (usually occurs to those with the most severe form of FGM):

- Problems passing urine. In severe cases, a person is left with only a small opening for urinating and menstrual bleeding. This can slow or strain the normal flow of urine, which can cause infections.

- Not being able to have sexual intercourse normally. The most severe form of FGM leaves a person with scars that cover most of their vagina. This makes sex very painful. These scars can also develop into bumps (cysts or abscesses) or thickened scars (keloids) that can be uncomfortable.

- Problems with gynecological health. A person who has undergone FGM sometimes has painful menstruation. They may not be able to pass all of their menstrual blood. They may also have repeated infections. It can also be difficult for a health care professional to examine a person’s reproductive organs if they have had a more severe form of FGM. Normal tools cannot be used to perform a Pap test or a pelvic exam.

- Increased risk of cervical sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV. People who have no medical training, under unclean conditions, perform most forms of FGM. Many times, one tool is used for several procedures without sterilization. These conditions greatly increase the chance of spreading life-threatening infections such as hepatitis and HIV. Also, damage to the person’s sex organs during FGM can make the tissue more likely to tear during sex, which could also increase risk of STIs or HIV.

- Problems getting pregnant, and problems during pregnancy and labour. Infertility rates among people who have undergone FGM are as high as 25 to 30% and are mostly related to problems with being able to achieve sexual intercourse. The scar that covers the vagina makes this very difficult. Once pregnant, a person can have drawn out labour, tears, heavy bleeding, and infection during delivery which cause distress to the infant and the mother. Health care professionals who are unfamiliar with the scar will sometimes recommend a cesarean section. This is not necessary as an expectant mother will be able to deliver vaginally once the scar is cut open.

Mental Health & Wellbeing Implications:

FGM also affects mental health. Case histories and personal accounts from people note that FGM is an extremely traumatic experience that stays with them for the rest of their lives.

Research carried out in Dakar, Senegal (see FGM Trauma.pdf (taskforcefgm.de))confirmed that people who had undergone FGM showed an appreciably higher occurrence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (30.4%) and other psychiatric symptoms (47.9%), than those which had not undergone the procedure.

Practitioners should be aware of the potential manifestations of psychological dysfunction presenting with victims of FGM. Whilst many people presenting for counselling who have been victims of childhood abuse display symptoms of PTSD, this diagnosis is not the only psychological difficulty that victims may encounter. They also include:

- FGM may be a contributory factor for psychological distress

- Presenting issue may be something different

- Feelings of ‘nothingness / incompleteness/ anxiety/low self esteem

- Lack of trust

- Anger or depression resulting from suppression of anger

- Fear of marriage and sexual relationships

- Fear of childbirth

- Loss

- Fear for their daughters

- Denial of sexuality and focus on reproductive functions

- Flashbacks

- Lack of sexual responsiveness

The above is not an exhaustive list,

Links to forced marriage and honour based violence

A forced marriage is where one or both people do not (or in cases of people with learning disabilities or reduced capacity, cannot) consent to the marriage as they are pressurised, or abuse is used, to force them to do so. It is recognised in the UK as a form of domestic or child abuse and a serious abuse of human rights.

The pressure put on people to marry against their will can be physical (including threats of intimidation, actual physical violence and sexual violence) or emotional and psychological (for example, when someone is made to feel like they’re bringing shame on their family). Financial abuse can also be a factor.

For more information visit:

- https://www.gov.uk/forced-marriage

- https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/322310/HMG_Statutory_Guidance_publication_180614_Final.pdf

In certain communities, it is considered important that a person undergo FGM before being able to marry. Usually this will be performed during childhood, but nationally there have been reports of people undergoing FGM just before a forced marriage.

‘Honour’ based violence (HBV) occurs when perpetrators believe a relative or other individual has shamed or damaged a family’s or community’s ‘honour’ or reputation (known in some communities as izzat), and that the only way to redeem the damaged ‘honour’ is to punish the individual which may result in severe injury or death. HBV is a term that is widely used to describe this sort of abuse; however it is often referred to as ‘honour’ based violence because the concept of ‘honour’ is used by perpetrators to make excuses for their abuse.

There is a strong link between ‘honour’ based violence, forced marriage and domestic abuse (please also see the NYSCP Domestic Abuse Practice Guidance). Examples of ‘damaged honour’ are:

- Defying parental authority

- Becoming overly westernised in style (e.g. clothing, make up, behaviour, attitudes, etc.)

- Having sex/relationships/pregnancies outside marriage

- Using drugs, alcohol, cigarettes

- Family honour can be damaged by unfounded or untrue gossip or rumours

- Interfaith or intercommunity relationships

- Leaving a spouse or seeking a divorce

In order to control the actions of children, young people and adults either to prevent a person from bringing shame to a family or community, or punish them for doing so, FGM may be used.

Other forms of ‘honour’ based violence can include, but are not limited to:

- Being disowned or ostracised by the community

- Physical abuse of the victim by family members including spouse and in laws (please also see NYSCP Domestic Abuse Practice Guidance)

- Restriction of freedom or loss of independence – being “policed” by family members

- Isolation from wider family or community, e.g. stopped from seeing friends

- Forced marriage

- Murder

Internalisation of guilt or shame by the victim can cause internal conflict for them, and not wanting to cause further shame can result in self-harm and suicide attempts.

Useful numbers

Afruca-Africans Unite Against Child Abuse

Unit 3D/F, Leroy House,

436 Essex Road

London, N1 3QP

Tel: 0207 704 2261

Email: info@afruka.org

Website: www.afruka.org

Black Health Initiative (BHI)

231 Chapeltown Road

Leeds LS7 3DX

Tel: 0113 3070300

Website: www.blackhealthinitiative.org

Black Women’s Health & Family Support

First Floor

82 Russia Lane

London

E2 9LU

Tel: 020 8980 3503

Email: bwhafs@btconnect.com

Website: http://www.bwhafs.com

Childline

Tel: 0800 1111

Website: www.childline.org.uk

FORWARD- Foundation for Women’s Health Research and Development

Suite 2.1

Chandelier Building

8 Scrubs Lane

London

NW10 6RB

Tel: 020 8960 4000

E-mail: forward@forwarduk.org.uk

Website: www.forwarduk.org.uk

Halo Project

The Halo Project, an award-winning specialist service provider supporting Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) victims and survivors of illegal cultural harms, such as forced marriage, female genital mutilation and honour-based abuse, has partnered with Yorkshire’s largest domestic abuse and sexual violence charity, IDAS, to intensify the level of support offered to victims and survivors across the region.

For more information visit:

Home Office FGM Unit

Tel: 0800 028 3550

Email: fgmenquiries@homeoffice.gsi.gov.uk

Website: www.gov.uk/government/collections/female-genital-mutilation

IDAS

IDAS is the largest specialist charity in Yorkshire supporting people affected by domestic abuse and sexual violence.

NSPCC FGM Helpline

Tel: 0800 028 3550 (24 hour free helpline)

Email: fgmhelp@nspcc.org.uk

Website: www.NSPCC.org.uk

References and Further Reading

WHO Female Genital Cutting Key Fact Sheet

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation

Eliminating Female genital mutilation, World Health Organisation

FGM Key Facts, World Health Organisation

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/

Female Genital Mutilation – The Facts, HMG

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/female-genital-mutilation-leaflet

View all our news

View all our news